The Significance of Mice in the Diet of the Tumbuka, People of Eastern Zambia

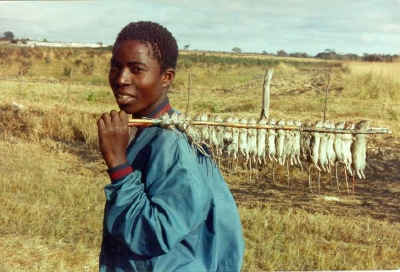

The hunting and eating of mice is very deeply entrenched in the customs and traditions of the Tumbuka people of Eastern rural Zambia. As a delicacy, mice might be offered with the nshima staple traditional meal, which is cooked by boiling plain water and stirring corn meal into it until the mixture is thick. The meal with mice might be served to guests, other respected elders, or eaten by the family as a special treat. A shrewd housewife will know to properly budget and ration the mice. If there is a difficult choice a wise wife who is worth her esteem is expected to reserve some for her husband if she loves and respects him. Common expressions among the Tumbuka include a couple yearning or wishing for a baby boy so that he can kill mice for them when he grows up. Parents chastise boys who bully their little sisters by telling them: “Who is going to cook mice for you when you grow up?” One of the traditional criteria for a boy growing to manhood was the ability to dig for and kill mice. If a child is running and accidentally trips and falls, an adult will console the child by dusting him or her and saying: “Never mind, you killed a mouse.”

There is a famous legend among the Tumbuka that illustrates how embedded the mouse consumption as a dietary practice is in the culture of the people. A man went to the fields and caught six mice. He brought them home to the village for his wife to cook. They were nicely dried. The man ate two of them with nshima and enjoyed them a great deal. The next meal, to the husband’s chagrin, he was served the nshima meal with delele green leaf vegetables. He angrily summoned his wife for an explanation. The husband stated that there were six mice, he had only eaten two. He asked where the other four had gone. The poor wife explained that she and the children had eaten two and her uncle and other guests who had visited earlier had eaten the other two. The husband proceeded to give the wife a beating for being so irresponsible. The wife proceeded to wail saying that her brute of a husband was killing her because of mbeba or mice.

In the village court, the elders severely rebuked the husband. He was so disgraced in his village and those surrounding ones because he was trying to run w hat was going on in the kitchen and particularly the kitchen pot which was hardly a man’s responsibility. From that time, men never count pieces of meat in the kitchen pot be it beef, chicken, small birds, or eggs. The mice legend plays many functions among the Tumbuka people. It defines limits of behavior between married men and women, reaffirms sexual division of labor and responsibilities, and discourages excesses in terms of husbands physically abusing their wives. The punishment for an erring husband will be public shame and disgrace.

Mice Consuming Population

Before the advent of Western influence through European colonialism, all African peoples developed their own sources of food. One such food, which has always been an excellent seasonal source of protein in rural Zambia, is the mouse. Most of the rural inhabitants of the Eastern Province of rural Zambia and parts of Northern Malawi, an estimated population of over one million, traditionally eat mice as a delicacy. These include such tribes as the Tumbuka, Senga, Chewa, Ngoni, and the Nsenga peoples. Although most of this material was obtained through the field work among the Tumbuka people of the Lundazi district of the Eastern Province of rural Zambia, the customs, attitudes, practices, and cultural beliefs that surround the mice consumption in the diet apply to most of the identified tribes.

As with any other cultural practice that has evolved perhaps over hundreds of years, the Tumbuka are very specific about what they eat. They would cringe and be as reviled as anyone else at the suggestion that they eat rats which are known variously in the indigenous languages of the Eastern Province as majancha or makhoswe. The Tumbuka detest the house rat as dirty, carrying disease, chews at clothes and any valuable household items destroying them and has to be killed and discarded at every opportunity.

The mouse on the other hand, known as mbeba, is found in the wild and lives on roots, nuts and berries. Mice are also especially found in large numbers in gardens where they can feed on peanuts, corn, sweet potatoes, peas, cassava. Indeed, agronomists often estimate that, a good percentage of the annual food harvest in many rural areas of Africa, is sometimes destroyed by such pests as insects, elephants, wild pigs, monkeys, birds, mice and domestic animals.

Types of Mice

The Tumbuka identify more than fourteen major types or breeds of mice, all of which, are edible. These include thodwe, kabwanda, kamzumi, kapuku, tondo, mphundu, sakachulu, julungwere, damba, chivuku, chitute, kambinini or kafula-fula, and kabwira. Thodwe has a rich reddish brown back and a white stomach. It burrows in sandy soils in and outside the garden. It is a solitary mouse except when it is on heat and nursing young ones. It is second in speed when running to the tondo type of mouse. Kabwanda is a very small mouse that burrows very deep into the ground. It has a lot of fat and is a highly prized and sought after breed.

Kamzumi, also known a fuko, is a grayish mouse with large protruding sharp teeth. It burrows endless long shallow holes in wet sandy dambos and stream valleys. The kapuku is a small mouse which hardly runs once it is flushed out of the hole. They are found in land types where cereal related foods and grass are plenty. Its distinguishing behavioral feature is that there can be twenty-five to fifty kapuku mice in one single hole which makes the job of the hunter relatively easy. The tondo is perhaps the fastest mouse known in the area. It has a long nose and makes clear narrow paths through which it always travels to and from fetching food. Mphundu mice often burrow several of them in one hole. They are difficult to catch as they disperse through numerous mibuli escape holes once diggers close in. Sakachulu mice burrow in anthills.

Julungwere mice have dark and brown stripes. It is a beautiful type kapuku-like mouse that feeds both during day and nighttime. Chitute are fat cheeked mice that pick, collect, and eat just about anything. In its hole hunters may find stored away human hair, beads, and other odd objects from the villages. When the Tumbuka and Chewa people of Eastern Zambia rebuke anybody by saying: “Don’t eat like a chitute”, they mean that the person should not be greedy.

Kambinini or kafula-fula mice exhibit behavioral characteristics like those of the kamzumi mice. Kambinini often make several furrows on one spot and any one hole might have up to a hundred mice. Once the diggers close in, the mice all escape out of the hole, run and scatter in all directions confusing the hunters. Kabwira is perhaps one of the tinniest mice known. If mice hunters kill the kabwira, the Tumbuka believe it to be a sign of bad luck.

Mice Hunting Techniques

Mice are hunted during the dry season from April up to early November. Men and especially boys have the responsibility of hunting mice. Catching mice requires tremendous skill and sometimes tenacity as when an individual is digging for the kabwanda that burrows really deep into solid dry hard clay soil. In this case the hunting party has do dig hard for long hours. The boys and men have to know what type of holes in the ground are likely to have what breed of mice, how to dig for them, how soil mixed with fresh mice urine smells like. If the odor is strong and fresh that is usually a good sign that the mice are in the hole. The boys have to know how to skillfully use short sticks or clubs, mphici, to strike the mice when they scramble out of the escape hole, known as mbuli, in their desperate search for new cover.

As the boys are digging, there are many ways of detecting the presence of mice in the hole. These include the smell of urine in the fresh dirt, mala fresh food storage, the presence of mphapanya which are ticks or fleas found together with their mala or food storage. Lastly, kutokosa, which involves softly shoving a small, long stick, into the hole several times. If the tip of the stick has what looks like mice hair on it, the hunters then conclude that the mice are in the hole.

Hunting for mice has serious, and in some cases, life threatening dangers. Depending on the nature and size of the mice hole, it could be home of stinging black ants, scorpions, spiders, wasps, lizards, and some of the most poisonous snakes known in Zambia. The men must be cautious and be aware of the various tell tale signs of potential danger. For example, if the men and boys are digging mice just after a big wild bush fire, it is likely that besides mice, scorpions, stinging ants, and snakes could be seeking refuge in the same hole. If a mice hole is large, shallow, and parallel to the ground, the diggers should be cautious.

One famous story that is told to young boys is that of a twelve-year-old boy who did not heed the advice of the elders as well as his peers. He wanted to be daring. The boy accidentally clutched a seven-foot mbobo snake by the neck mistaking it for an escaping mouse. This is said to be the deadliest and perhaps fastest snake known. Elders, often in a hush hush excited tone, describe how when provoked the mbobo snake can stand on its tail while chasing a man. The boy tried to squeeze the snake to death with all his might with the one hand. He failed. His terrified friends fled home in panic. The boy escaped certain death by running away and eluding the snake several times in the under brush. This story is meant to warn young mice hunters to be always aware of danger.

Sometime a group of several boys from different households or even villages will go hunting for mice. By sheer coincidence or bad luck they might only catch one mouse. They could not possibly cut it into many tiny pieces to be divided equally. The solution is the challenging and rather exciting practice of ponda. The boys place the mouse on a three-foot vertical stake perhaps more than fifty to a hundred meters away. Who ever hits the mouse off the steak using a short stick or mphici is the winner of the contest and gets the prize of the lone mouse. If it takes a long time for someone to hit the target, the boys might continue the contest until dusk and continue if there is moon light.

Over three decades ago, one of the easiest ways to catch mice was at the mkukwe. During the harvesting of the corn staple food, the common traditional practice was to cut all the dry maize stalks in the field in April. These were vertically placed in many huge piles in each field. Such piles are known as mikukwe. The corn staid there for two months. When the corn was finally harvested in June, the mice will have been breeding and made shelters in the corn and above ground. As the people picked each individual corn stalk from the mkukwe to remove the dry corn cobs, they would pick off the mice. With the increasing pressures from the modern economies, this practice has virtually disappeared. Since most rural farmers now have to rush their surplus harvest to commercial markets soon after the rains, there is no time for the traditional mkukwe practice anymore. If it is practiced at all it is for a very short period of about two weeks. This is hardly enough time for the mice to settle and breed in the corn. Due to pressures of the modern cash crop economy, quick and improved methods of food processing, and expanding population of as high as 3% per annum, it would not be surprising if the mice population has actually declined over the last two decades.

In addition to mice of the mkukwe type, there are several other ways in which the Tumbuka identify mice by how they are hunted. Mbeba zogima (mice of digging) are mice that are hunted through digging them out of their holes. Mbeba zavikuse (mice of grass and stalks pile) are mice which are hunted from from their hiding places in piles of dry stalks of corn, peanuts, beans and other stalks found in the gardens after the harvest. Mbeba zavisale (mice of the traps) are mice caught through the laying of special traditional traps made out wood set with bait known as nyambo. The traps are usually set in tall grass after the onset of rains in December and January over night in the bush.

Mbeba zakutegha muchibiya na maji (mice trapped in a clay pot with water) are mice which are caught through special traps set by laying clay pots with water in them in the bush. Nyambo or bait is suspended on top of the pots of water. The mice slip and fall into the water when they try to eat the bait. The mice then drown in the pots and are collected later. This method is rarely used among the Tumbuka.

How to Cook Mice

The cooking of the mice is very simple. The mice are gutted, boiled in plain water for about half an hour and salted. They are then fire dried until they are nearly bone dry. Mice are never cooked any other way. In fact, there is a song among the Tumbuka, whose lyrics are in the Chewa or Nyanja language, which mocks a young modern housewife who did not know proper mouse cooking.

Ena sadziwa kuphika lelo Ku mbeba

Ena sadziwa kuphika lelo ku mbeba

Anyenzi, tomato, komweko lelo ku mbeba

Anyenzi, saladi, komweko lelo ku mbeba

Some do not know how to cook mice

Some do not know how to cook mice

Onion, tomatoes in the mice

Onion, cooking oil in the mice

In the song, the grave mistake the young housewife apparently committed was to assume she could add onions, tomatoes, and cooking oil to the mice. These ingredients are highly valued in modern popular Zambian cuisine such as beef and chicken stew. But they are a taboo in cooking mice.

Among the many traditional sayings of the wise among the Tumbuka is:

Kambeba kasoni kakafwila kukhululu

A shy mouse died in the hole.

This saying is used to encourage individuals who are shy to act. After all the mouse that was too shy to do anything when the hunters were closing in died in the hole even without trying to scramble out to escape. Indeed many mice escape to safety from hunters especially if they run into the nearest thick under brush. Individuals who are indecisive may be urged to be more forthcoming when the saying is used to them.

Mice and Social Change

Compared to beef, chicken, or mutton, mice still remain by far the cheapest source of otherwise scarce and costly protein. Mice costs about K5.00 (Zambian Kwacha) (1991 value of the Kwacha) each in the rural areas and up to K50.00 (Zambian Kwacha) in taverns, beerhalls, and townships of urban areas where the mice are fondly called “Zambian sausages”. The average cost of beef in Zambia ranges from K120.00 (Zambian Kwacha) to K240.00 per lb. An average chicken costs about K600.00 or K200.00 per lb. These numbers may not have meaning to outsiders until you realize that the country has an annual inflation rate of 50% to 120%. The majority of urban dwellers earn an equivalent of Fifty US Dollars per month or less. Most rural people do not have any regular source of cash income. Perhaps the most dramatic way of illustrating the high cost of meat is if the cost of beef was $100.00 per lb. but most salaries remained the same or inflation was rising at 100%. Raising goats, pigs, beef, chickens is often difficult and might require expensive inputs and labor. Meat from wild animals like deer, rabbits, wild pigs, is on the decline due to the rise in population and increased use of high-powered firearms especially by poachers from urban areas. In many parts of rural Zambia, domestic animals often compete with humans for scarce grazing land, water and food. The domestic animals are rarely a cost efficient and generous way of obtaining protein. In rural regions where there is tsetsefly, it might be virtually impossible to raise domestic animals like cattle.

Mice therefore are one of the few valuable remaining sources of protein. European colonialism and other modern influences have sometimes introduced serious inferiority complexes among indigenous peoples. As modern influences penetrate rural traditional areas in Zambia through increased urbanization, the eating of this type of traditional food might decline as indigenous people begin to believe that eating mice is somewhat inferior to eating, say beef or a hamburger.

About the Author =

Mwizenge S. Tembo obtained his B.A in Sociology and Psychology at University of Zambia in 1976, M.A , Ph. D. at Michigan State University in Sociology in 1987. He was a Lecturer and Research Fellow at the Institute of African Studies of the University of Zambia from 1977 to 1990. During this period he conducted extensive research and field work in rural Zambia particularly in the Eastern and Southern Provinces of the country. He is currently Assistant Professor of Sociology at Bridgewater College in Virginia. This material was gathered during a research field trips (1980 and 1985) sponsored by the Institute for African Studies and in August 1993 partially sponsored by a grant from the Bridgewater College Flory Development Fund and supported by the Institute of African Studies of the University of Zambia to whom he is very grateful. Thanks to all respondents in the villages and the Lundazi District Governor’s office.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: The author would like to thank Dr. Mapopa Mtonga, Lecturer in Theater and Performing Arts at the University of Zambia, for his suggestions and comments on this article.